Art, as High Art, developed in the West at the end of the 18th century, when objects with certain distinctive formal attributes and cultural significance began to be considered as belonging to a sphere beyond the everyday phenomenal world. Boris Groys has suggested that the creation of art museums in the 19th century encouraged western artist to create works whose sole function and purpose was to be showcased as "art." Scrutinizing and problematizing the artworld and the institutions that determined which subjects and aesthetic modes are counted as Art, became one of the main thrusts of contemporary art after the 1960s. Nevertheless, the mainstream modernist definitions of the term have not completely lost their currency.

The advent of the film camera and projector at the end of the 19th century reflected a new interest in movement and changing ideas about time and the nature of the universe that contested an ontology and epistemology structured around the belief in stable entities (objects) that resulted from the combination of matter and form (hylomorphism.) Animation derives from the Latin anima, that is, the soul and, in general, the incorporeal essence of a living being. Animation is a time-based moving image form. As animators create pre-filmic material using fine arts techniques and materials, this form is free from the expectation to realistically represent the world that haunts live film. In the early 20th century, animation was understood as a subsidiary film form related to graphic cartoons, magic, vaudeville, and the entertainment industry. Its place in culture changed dramatically with the advent of digital technology: in the 21st century, animation is pervasive and practically omnipresent in everyday life. As an artistic expression, animation challenges traditional approaches to art and explores motion as a way of expanding the materiality of physical objects central in western ontology and epistemology. In this way, animation favors an understanding of the universe as an interplay of intensities and entities in constant flux.

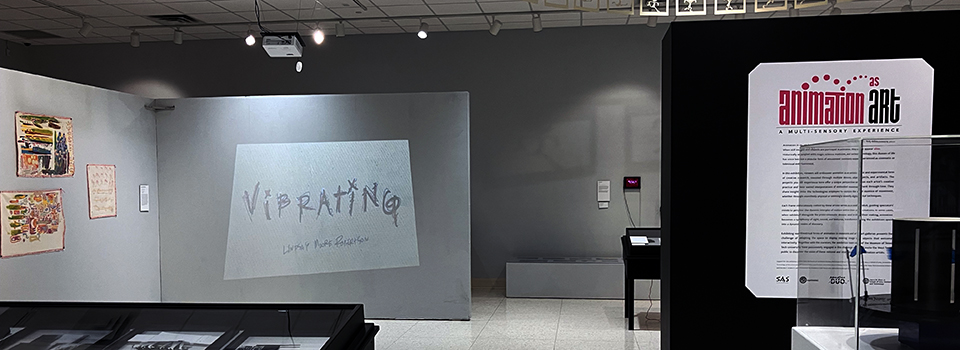

The exhibition aimed at illuminating the animators' creative process by presenting their pro-filmic (phenomenal) materials together with the finished animations as well as devices that create the illusion of movement out of static images. Torre, for example, engraved glass goblets with figures representing the phases of a bird's flight, while in Álvarez Sarrat's work objects from her personal archive of found materials and outmoded images protagonize bizarre little adventures. Koning's mix of 3D printed objects and natural materials, challenges the demarcation between the real and the virtual whilst Everest's doll, inspired on those in the Manchester Art Galleries' collection, tries to escape the box where it is preserved, reminding us of what might go on at night in the Museum. Bansal's animation happens in the exhibition as the public examines and discards sheets from a stack of papers while Woloshen displays the instruments he uses to create his abstract animations, thereby proposing a Deleuzian assemblage that brings together the real and a multitude of virtual worlds.

Different philosophical approaches to the notion of experience influenced the development of modern art. In the early decades of the 20th century, W. Benjamin reflected on how modern life and technology—of which film and animation were clear manifestations—had affected the nature of human experience; at mid-century, phenomenology countered the primacy of vision and theorized the multisensory nature of perception and the embodied nature human experience; since the turn of the 21st century, new media theory explores how digital and computer technology shape our experience. M. Hansen claims that new moving image art has the potential to make evident to spectators the obscure processes that create the fictional worlds and experiences that—disseminated through a myriad of media platforms— affect our sensibility. The theoretician claims that, in this context, ontology—that is being—is second to experience. This is not a new concept for animators: as film historian Joe Adamson once wrote, “Bugs Bunny does not exist. But he lives.”

These different approaches to experience are addressed by the artists in the exhibition: works inspired by "outmoded" pre-cinematic devices invited spectators to perceive and even create the movement that animate images (Cogua, Dolphin, Leeper, Mudassani, Mahoney, Najmi, Veras, Veras/Devadder); installations and interactive pieces addressed spectators as embodied viewers-participants (Bansal, Hosea, Horne, Yekti); and examples of projection mapping and virtual movement (García Moreno, Lee, Meador) challenged and enriched their perception of the world.

is an Art Historian from the School of Art at TTU, and co-founder of AnimationDuo and the Animation Making Workshops. She specializes in Animation History and Theory, Modernism, and the historiography of Art History and Animation.